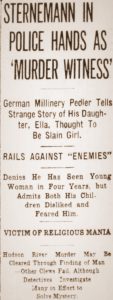

Sternemann in Police Hands as ‘Murder Witness’

German Millinery Pedler Tells Strange Story of His Daughter, Ella, Thought to be Slain Girl.

Rails Against “Enemies”

Denies He Has Seen Young Woman in Four Years, but Admits Both His Children Disliked and Feared Him.

Victim of Religious Mania

Hudson River Murder May Be Cleared Through Finding of Man – Other Clews Fail, Although Detectives Investigate Many in Effort to Solve Mystery.

Peter H. Sternemann, the eccentric peddler whose rambling, incoherent letters to the authorities investigating the Hudson River murder mystery were followed by his “disappearance” yesterday morning, was arrested in the office of “The New York Herald” early this morning as a material witness, pending an attempt to be made to identify the body as that of his daughter, Ella Sternemann.

Sternemann, except to explain that he “surmised” that the body might be that of his daughter, steadfastly denied to Assistant District Attorney Deacon Murphy, who examined him after his arrest, that he had seen her in the last four years, but he admitted having “heard” that she was in several places recently. This information came to him, he said, from “enemies” who were persecuting the Sternemann family and who were trying to “extinguish” his relatives.

Sternemann wet to Hoboken from his home, at 113 Globe avenue, Jamaica, Long Island, yesterday, in company with a reporter for The Tribune.

The aged German millinery peddler was found at his home, where he had two unfurnished rooms, early yesterday morning by a Tribune reporter. He had come in at 1:30 o’clock in the morning after a log round of business calls in the Bronx, where he sold feathers and millinery trimmings to small retailers.

Became Greatly Agitated.

When he was told the mission of his visitor Sternemann became greatly agitated. It was explained that it was necessary for him to go to the morgue in Hoboken to try to identify the torso of the slain girl, and when the prospect of the trip was realized he begged for water, complaining of fainting spells. He was revived and then accompanied The Tribune reporter to Meyer’s Hotel, at 3d and Washington streets, Hoboken.

In a room of the hotel he rehearsed at great length and with many variations a long, almost non-understandable account of many troubles and persecutions with which he said he had been afflicted. In none of his statements, however, would he say that he had seen his daughter Ella since she “ran away from him four years ago.”

When he had spent most of the day in his rambling story he first expressed a desire to go to Volk’s morgue, and them immediately changed his mind. The ordeal, he thought, would be too much for him without a rest. He feared his “enemies” had followed him to the Hoboken hotel and insisted that he go to Newark. He was accordingly accompanied to a hotel in Newark, where he finally became convinced that the best plan for him was to communicate with the police.

Sternemann’s mother and father, both of whom died while insane, were Alsation Germans, and Sternemann was born in Germany fifty-seven years ago. According to his story he has been peddling feathers and millinery trimmings for thirty years.

“All my life,” Sternemann said yesterday, “I have been worried by my family troubles and by my daughters. It is for this reason that I think my daughter has come to some unfortunate end. If she has got into bad hands it may be that it is better that she is dead. It would be a blessing if she were not to be persecuted by the enemies who have fought us all.”

Says Daughter Feared Him.

Sternemann said that he had not seen his daughter since she was employed in the home of Mrs. Emily Schaeffer, at 23d street and Third avenue, four years ago. She ran away from there, he admitted, because she did not want to see him, and feared him, for some reason Sternemann could not explain.

She then went to the home of his half-brother, Henry Sternemann, who lives at No. 304 North Terrace, Mount Vernon, N. Y. This brother, Sternemann said, would not tell him where his daughter lived, and from that time, he said, he has not seen her.

From other sources, usually through his other daughter, Emma, now in the Kings Park State Hospital for the Insane, Sternemann says he learned that Ella was employed by Mrs. Wittaker North, who then lived at Metropolitan and Church avenues, Richmond Hill, Long Island. Later he thought she worked in a theatrical costumer’s establishment, and may, he thought, have gone on the stage.

Nine months ago, he said, Emma told him that through his brother, Henry, she learned that Ella was in New York City. Where the daughter was living, Sternemann said, Henry would not say, and Sternemann did not try to seek further for her.

Nine weeks ago, in the vicinity of 146th street and Eighth avenue, where the pillow slip in which part of the body was found was purchased, Sternemann said, he saw a “googly eyed fellow” with a girl who he thought was Ella. Last week he returned to the same neighborhood and saw the “googly eyed fellow” in a shoe store. Sternemann admitted that he frequently was at Eighth avenue near 146th street selling feathers.

Of his action in the last week Sternemann is only sure that he went nearly all over the upper east and west sides of Manhattan, and through Brooklyn and Queens, on his peddling rounds. Until Thursday he lived at No. 27 Olive street, Brooklyn, but had been put out for not paying his rent.

Moves to New Home.

Through a German newspaper he communicated with Mrs. Mathilda Weiss, in whose home, at No. 113 Globe street, Jamaica. Sternemann last lived. He moved into his new home Thursday night, bringing with him great quantities of cheap finery, an iron stove, two heavily padlocked boxes and household furniture, in which were included a cheap bedstead and a pine table.

Friday he peddled, not returning until late at night. Saturday he went to Manhattan and worked along Third avenue, and while there he sent the letters to Chief of Police Hays and Volk, the undertaker.

Early Sunday morning, he said, he got up and washed out a pair of trousers, a shirt, underclothing, an old table cover and a burlap bag. Then he painted the table and bedstead with white enamel paint.

His only explanation for painting the table and bedstead was that they were “dirty.” There were no stains, he insisted, which he wished to conceal, and his desire to have them “clean” was in preparation for the homecoming of his daughter Emma from the asylum. He added that he did not expect Emma home for more that a month.

His explanation of his washing of the clothes was similarly indefinite. Although he had several other pairs of trousers, he said he wanted to wear the particular pair he had washed. The burlap bag, he said, had been “dirtied” by contact with the iron stove and because it had contained shoes, and the tablecloth, which was worn to raggedness and was of no value, he said, he wished to preserve in order to sell with his hat trimmings.

As told in The Tribune yesterday there were also found in his room a quantity of milliner’s wire, similar to that which was wrapped around the torso, a coil of clothes rope, identified as similar to that also used to enwrap the bundle, a new wood saw, two butchers’ knives, with the edges but slightly dulled, and a carpenter’s chisel, with several nicks in the blade.

Vague in Statements.

Sternemann at first had ready explanations for the possession of each of the articles, and afterward became vague in his statements. The wire, he said, Emma had gathered up before she went to the hospital two months ago; he had no special reason for having the rope, which was new and not unwound; while the saw, knives and chisel, he said, he had bought five months ago, in expectation that some time in the future he would go on a farm and would need these tools. While he had been housekeeping with Emma at No. 27 Olive street before she went to the asylum, he said, he never had occasion to use either the butcher knives or the other tools.

When it was suggested that in his condition of poverty the purchase of expensive articles was a foolish one, Sternemann replied that he was never too poor to buy things he needed.

Sternemann’s rooms were crowded with old letters, boxes of millinery, articles without apparent value, and hundreds of odds and ends which he had gathered loosely together. Several Bibles and extracts therefrom were found. Sternemann said he was a devout Catholic.

“I was too strict with my girls,” he said, “and when they did wrong and I reprimanded them they would get angry with me. That was why they turned against me to go with my second wife, from whom I separated. That woman led them into trouble. She is dead now, but her influence on the girls has made most of my troubles. I often scolded Ella for being wayward and tried to teach her religion.”

Throughout his conversation with The Tribune reporter yesterday Sternemann was unable to answer my question without the interjection of irrelevancy and incomprehensible statements. His speech was that of a man with the thought of constant oppression preying upon his mind to the extent that he could think of little else.

If the touch of insanity which ran through his family has not been manifested in him, his remarks about his “enemies” show unbalanced thought. He accused every one of whom he spoke of having cheated him out of money, and he thought a band of Italians was following him, paid by a man with whom he quarreled after lending the man money. He said that probably the police were shielding those who were trying to “exterminate” him, as he expressed it.

Held Daughter’s Money.

His money affairs, particularly with two sums of $188 each, left to his daughters by his first wife, of which he was the trustee, were tangled and hard to account for. The money was deposited in the Germania Bank, in New York, he said. When the man he mentioned wished to borrow the money, Sternemann, he said, without his daughters’ consent, withdrew all but $3 and gave the man $198. The rest, Sternemann added, he used to “speculate in feathers.”

Ella, the daughter, he thinks, was identical with the girl whose body was found, never asked him for any of this money, Sternemann said. While he knew that she was reported to be in want and had been put out of several places, he admits that he never made any attempt to find her or pay her any of the money which was entrusted to him. Why she had not appealed to him for assistance he could not understand.

For years, he said, he worried about the disappearance of Ella, but while he wrote letters to the police whenever a woman’s body was found he never went to a morgue to try to identify it. He stayed away from the Hoboken morgue, he said, because he didn’t want to take the trouble unless there was some chance it might be his daughter.

“Maybe I made a mistake,” he said, “but I didn’t want to spend the money. Of course, it cost me 30 cents in postage stamps, but I couldn’t spend the time from my millinery business.”